Asbestos exposure is the single largest on-the-job killer in Canada, accounting for more than a third of total workplace death claims approved last year and nearly a third since 1996, new national data obtained by The Globe and Mail show. The 368 death claims last year alone represent a higher number than fatalities from highway accidents, fires and chemical exposures combined.

Asbestos exposure is the single largest on-the-job killer in Canada, accounting for more than a third of total workplace death claims approved last year and nearly a third since 1996, new national data obtained by The Globe and Mail show. The 368 death claims last year alone represent a higher number than fatalities from highway accidents, fires and chemical exposures combined.

Since 1996, almost 5,000 approved death claims stem from asbestos exposure, making it by far the top source of workplace death in Canada.

The numbers come as the federal government – long a supporter of the asbestos industry – continues to allow the import of asbestos-containing products such as pipes and brake pads. A Globe and Mail investigation earlier this year detailed how Ottawa has failed to caution its citizens about the impact that even low levels of asbestos can have on human health. Canada’s government does not clearly state that all forms of asbestos are known human carcinogens. Dozens of other countries including Australia, Britain, Japan and Sweden have banned asbestos.

Canada was one of the world’s largest exporters of asbestos for decades, until 2011, when the last mine in Quebec closed. The mineral’s legacy remains, as it was widely used in everything from attic insulation to modelling clay in schools and car parts and in a variety of construction materials such as cement, tiles and shingles. Health experts warn long latency periods mean deaths from asbestos will climb further.

“The indications are that we can expect an increase [in asbestos-related diseases] to continue for at least another decade or so. And that’s assuming we as a nation ban it now. If we don’t do that, we can expect it to continue to rise indefinitely, but perhaps at a lower rate,” said Colin Soskolne, an Edmonton-based professor emeritus at the University of Alberta.

In Australia, which banned asbestos in 2003, asbestos-related diseases continue to climb. The “responsible public-health action would be to ban the use of asbestos in Canada and other countries and replace it with substitutes,” said Dr. Soskolne, who is also chair of the International Joint Policy Committee of the Societies of Epidemiology, adding that there is “no demonstrated safe way to use it in Canada.”

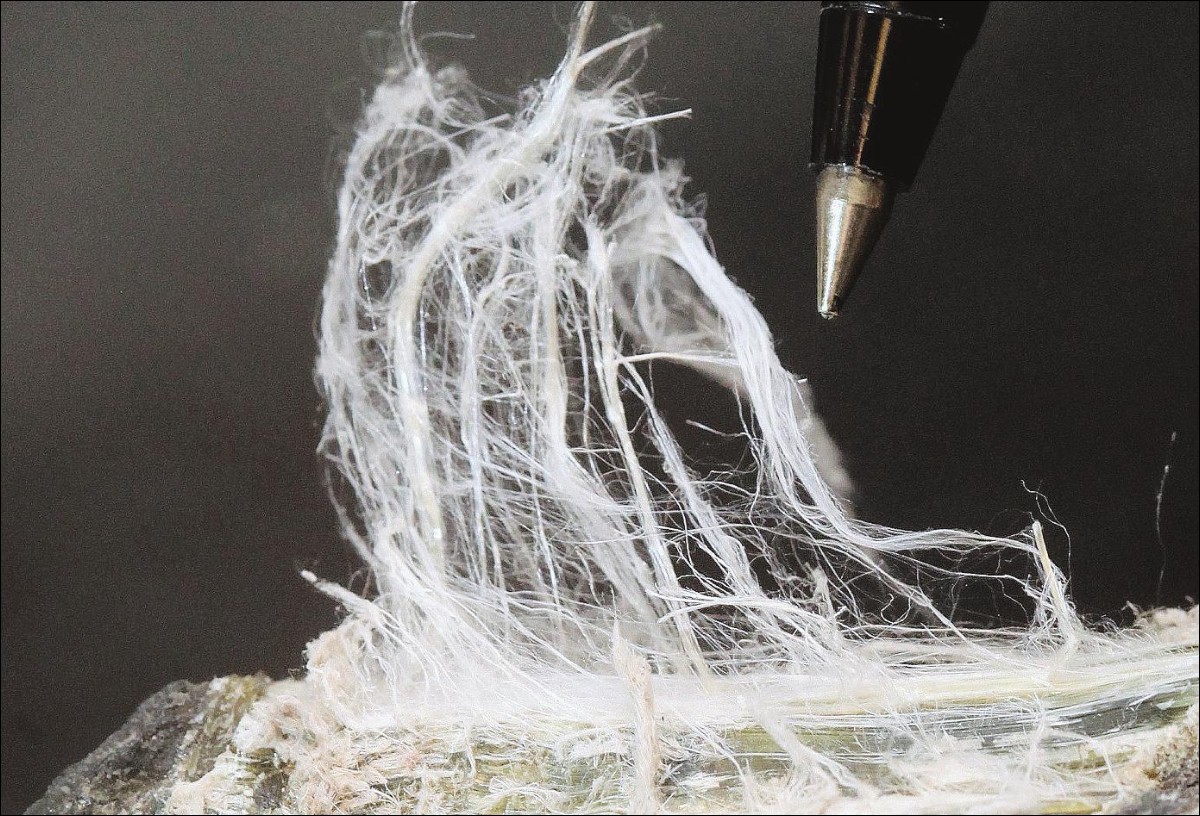

Asbestos-related diseases have a long latency period of typically 20 to 40 years. Many victims die of mesothelioma, an aggressive form of cancer caused almost exclusively by exposure to asbestos, and asbestosis, a fibrosis of the lungs.

The data come from the Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada and is typically updated every fall. For 2013, the most recent year for which annual data are available, it shows the single greatest cause of death was mesothelioma, with 193 fatalities. Asbestosis was a factor in 82 deaths.

“There’s some misconception that we banned it – and we haven’t,” said Jim Brophy, former director of the Occupational Health Clinic for Ontario Workers in both Windsor and Sarnia. Canada now has “an enormous public-health tragedy, disaster on our hands.”

All commercial forms of asbestos including chrysotile, the type formerly mined and most commonly used in Canada, are classified as carcinogenic by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Its evidence shows there is no “safe” form of asbestos nor a threshold that it considers safe.

The agency’s position is at odds with Health Canada, whose website continues to play down the risks of asbestos exposure. It never clearly states that all forms of asbestos cause cancer, but rather that chrysotile asbestos is “less potent” than other forms and that there “is no significant health risk” if the fibres are enclosed or tightly bound.

“Asbestos poses potential health risks only when fibres are present in the air people breathe,” Health Canada says. The problem is there’s no way of ensuring that all products are always bound or enclosed. Brake pads wear down; renos stir up dust while pipes and tiles get sawed.

Britain’s national regulator for workplace health and safety informs its citizens that asbestos causes about 5,000 deaths per year – but there is no comparable information on Health Canada’s site. Health Canada told The Globe and Mail it has no plans to update its website, last revised in 2012.

And while the World Health Organization bluntly says “all types of asbestos cause lung cancer, mesothelioma, cancer of the larynx and ovary, and asbestosis,” Health Canada still says asbestos fibres “can potentially” cause asbestosis, mesothelioma and lung cancer “when inhaled in significant quantities.” The potential link between exposure to asbestos and other types of cancers “is less clear,” it adds.

The workers’ compensation numbers don’t fully capture the total number of fatalities in Canada as not everyone is covered by workers’ comp and not every claim is successful. Separate Statistics Canada data show almost 4,000 people died of mesothelioma alone in the decade to 2011.

Heidi von Palleske says the numbers also don’t capture wives and children who have been affected. She calls herself an asbestos orphan – her father died in 2007, with asbestosis and lung and prostate cancer. He was a former worker at a plant run by Johns Manville, which made asbestos-fibre products. Her mother, who shook out and washed her husband’s clothes for years, died of mesothelioma in 2011 and Ms. von Palleske’s sister and brother have since been diagnosed with pleural plaque (a calcification of the lungs).

“It’s inexcusable,” said Ms. von Palleske. She wants to see a ban and better supports for families affected by workplace exposure.

Miners were among the first to be affected, but the range of occupations with workers exposed has expanded in recent decades.

About 152,000 workers in Canada are currently exposed to asbestos, according to Carex Canada, a research project funded by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The five largest groups are specialty-trade contractors, building construction, auto repairs and maintenance, ship and boat building and remediation and waste management.

Source: The Globe and Mail